- Home

- Michael Lawrence

The Realities of Aldous U Page 9

The Realities of Aldous U Read online

Page 9

Mr. Dukas shook his head. ‘He’s not on it. I remember him saying, he had it taken out because the bloody thing kept ringing. I’ll go see him personally.’

When he’d gone, Liney sighed. ‘That’s the last we’ll hear from him,’ she said.

Day Four / 2

For Naia, yesterday had seemed endless, and, barely a third over, today was also dragging. Where was Alaric? Why didn’t he come? How long was she expected to wait in for him? Three friends had called separately to invite her to mess around in the snow and she’d excused herself each time. A heavy period was the one they most readily understood. By one o’clock she was seriously thinking of saying to hell with Alaric and going out anyway. When her mother asked if she fancied a walk in the snow she accepted, hoping the friends she’d put off wouldn’t see her and think she was avoiding them.

Day Four / 3

Liney was still messing about in the kitchen when Alaric made his excuses, donned his boots and parka at the front door, slammed it, and crept along the hall and up to his room. There, careful to make no sound at all, he crouched over the Folly with his hands around the dome. After yesterday’s failure he wasn’t at all certain of success, but he had to try. A second failure would mean once again having to tell Liney that he’d changed his mind about going out and, again, feeling obliged to help with the decorating. He concentrated those of his emotional energies that he could muster, but five minutes later was still there. In defeat it took a while to notice that the reflection in the dome wasn’t as it had been previously. He glanced at the window. It had stopped snowing. Well, that was it then. If snowfall was one of the factors that activated the Folly and they’d had all the snow they were going to get, there might be no more visits to Naia’s till next winter. And suppose there wasn’t any snow then? There were no guarantees with snow. It might not snow for years. Which meant that he might never return, never see…

He sat back on the arm of the chair. That was really what this was about. Who. The other Alex. All yesterday and this morning while working with Liney she’d never been far from his thoughts. The woman he’d grieved for and missed so desperately for so long was still alive, elsewhere. He’d heard her voice. If he’d stepped out onto Naia’s landing he would have seen her at the foot of the stairs, looking up, at him. But he hadn’t. He’d run for it.

He reached out and ran a finger lightly down the glass of the Folly, wishing that he could turn back time, just a little bit, look her in the eye, see that quick smile of hers, then go downstairs, touch her hand, and –

The tingle was so short-lived that he had no time to prepare for the pain that shot up his arm, blasted his insides, but – perhaps because the route was now established – the room vanished and he was sprawling in the snow under the tree almost before he realized what was happening.

‘Where did you spring from?’

Naia: bounding across the garden. She ran like Liney, the aunt she didn’t have, arms and legs all over the place.

He sat up, turning away so she wouldn’t see the last flicker of pain in his eyes. ‘Take a wild guess.’

‘But it’s stopped snowing!’

‘Yeah. One factor less.’ The only one I came up with, he thought.

‘So we’re not locked into the season or the climate. We can go on seeing one another all through the year.’

‘Yippee.’

‘I thought you’d have come before this.’

‘I was busy.’

His chest ached and his insides were shaking. He wanted nothing but to sit quiet till he felt right again, but started to rise because she was there. Naia reached down to help him up. He would have shrugged her off but she was too quick. As she gripped his arm an intense pain ripped through them – both of them – and they fell back as though kicked.

‘What was that?’

‘It was like an electric shock.’

They got to their feet. Alaric put a hand out. Naia jumped back.

‘Get off!’

‘We need to see if it’ll happen again,’ he said.

‘You might, I don’t.’

But he grabbed her arm. Again the current shivered through them.

‘Let go!’ Naia said. ‘Let go, it’s killing me!’

He gripped tighter, and as the pain continued to course through them his hand penetrated the material of her coat, then her arm, until it felt as though he was holding a tube of some sort. Naia, for her part, felt his hand enclosing the bone. She shook him off in horror. The current died.

‘That was disgusting!’ she said. ‘What was it?’

‘You tell me. What are we doing different this time?’

‘Have we ever touched before?’

‘I can’t remember.’

‘This is the first time we’ve been out of doors together.’

‘So?’

‘That could be the difference.’

‘Indoors, outdoors, no, too simple.’

‘Who says it has to be complicated? Have you been inside yet? I mean this time, today?’

‘Didn’t get a chance,’ he said. ‘You ran up just as I got here.’

‘Well that’s it then. Probably. You haven’t gone all the way yet.’

‘All the way?’

‘Your Folly sends you to my reality, mine sends me to yours, but we have to stop off in the garden on the way, yours or mine, depending which of us is making the trip. The gardens are sort of half-way points. You have to finish the journey. Won’t be fully integrated into my reality until my Folly receives you.’

‘There you go again,’ he said.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Your crazy theories.’

‘Crazy or not,’ Naia said, ‘at least I have some.’

‘What about those shocks? My hand sinking into your arm.’

‘Don’t know. Nature’s way of pointing out that we can’t co-exist at the half-way points? The pain when we set out from one reality to the other could be another hint that we’re defying a physical law or two.’

Alaric glanced at the house. ‘Where’s your mum?’

‘Trudging. So was I, but I turned back, thought I’d better hang around here in case… Where are you going?’

He’d set off toward the house. ‘Where’d you think?’

She ran after him, boots sinking into the snow.

‘Wait. Stop. You can’t get in that way.’

‘Why, is it locked?’

‘Yes. I told you, I was going out, saw you before I had a chance to unlock it, but that’s not what I mean.’

He stopped, turned, held out his hand. ‘Key.’

She also stopped, but kept her distance. ‘I’m not touching you again.’

‘Drop it on the ground then.’

She didn’t drop the key on the ground. ‘You can’t go in by the door,’ she said. ‘If you do, you’ll still not be quite here. ’

He looked away. She was right. Of course she was right, wasn’t she always? Annoyed that he hadn’t thought of it, he turned his back, glared at the house, imagined himself inside it.

And that was all it took. It was all it had ever taken.

Naia watched him fade until all that was left to show that he’d been there were his footprints – very shallow compared to hers. He’s inside, she thought. Up in my room. Making a mess of my carpet.

Day Four / 4

Alaric removed his snow-encrusted boots in Naia’s room and carried them down the recently recarpeted stairs. All about him, above and below, the house glowed with light and life and warmth. As it was his first time alone here he decided to make the most of it; but he couldn’t hang about. If he took too long Naia would almost certainly come looking for him; or worse, her mother might return and find him prowling about. Much as he wanted to meet this reality’s Alex Underwood, it was not as an assumed intruder.

Reaching the lower hall he turned left into the Long Room. These days this room at his Withern Rise was just a place to flop and watch TV, but the Long Room he ente

red had been redecorated and updated a few months earlier. At the far end, where logs spat and crackled behind an antique fireguard, he found a large plasma TV and a new couch and armchairs. He sighed, and

was about to leave when he saw the guitar. A Spanish acoustic of moderate quality, it leant casually against the wall as if set down moments before. His mother’s identical guitar had long since been confined to the attic with those others of her things that hadn’t been sold, given away or destroyed. Running a finger across the strings, Alaric imagined her playing quietly to herself, as she so often had when believing herself unobserved, unheard. Well, playing. The guitar was one of the few things she had put her hand to that she’d failed to master. Perhaps if she’d taken lessons she would have made more progress, but Alex Underwood preferred to be self-taught in all things where possible. She’d managed to pick up the basic chords, and a few of the more complex ones, but technique of any standard had eluded her. Alaric remembered mocking her efforts to her face, but he’d enjoyed hearing her plunking away in her hopeless pursuit of competence, somewhere in the house. Sometimes she would sing along, with a wavering, uncertain voice, to her elementary strumming or clumsy finger-picking. She was as poor a vocalist as she was a musician, yet for Alaric these things had been part of her. They’d been his mother.

He crossed the hall to the kitchen, where he found that the shoddy curtains had given way to elegant roller blinds, a multi-burner gas cooker to the greasy old range. There was a big new sink with shiny taps and double drainers, purpose-built units below, and the floor’s brittle old vinyl had been torn up, the boards it had concealed stripped and varnished. Instead of burnt and blackened pans, gleaming copper jugs, pots and utensils hung on hooks from the ceiling. There were shelves of recipe books, a classy breadmaker, a new microwave, and on the walls lots of kitcheny pictures, charts and memo pads. It was all so neat and bright and decent, and therefore depressing. The one remotely pleasing observation he could make was that the walls appeared to be the very color that he and Liney had used for his kitchen.

Withern was the only home Alaric had known, so it did not seem exceptional to him; but with its four tall chimneys, its enormous garden and river frontage, it was the sort of property usually occupied by moneyed folk. The Underwoods of this generation and the last were far from wealthy. If his parents had been burdened with a hefty mortgage they would have been in some difficulty much of the time. They’d always worked, but Alex had been very modestly paid for her part-time work at the college, and Ivan’s business had rarely done much more than tick over. If he’d thought about it, Alaric would have imagined that things were much the same for Naia’s family, but if that were so, where had the funds come from for all this new stuff and the work that had been done here?

Returning to the hall he stood with his back to the front door gazing down the long hallway, with its polished woodwork, its little side tables, a vase of flowers on one of them, and a terrible sadness welled up in him. This was the Withern Rise he would have known if his mother had lived. The house he would have come home to from school, woken up to, invited friends into. The home he would have taken for granted if his and Naia’s lives and luck had been reversed.

Day Four / 5

Naia didn’t expect her mother back yet, but she thought it best to stand guard outside just in case. She’d unlocked the front door and given him what seemed an eternity, and was about to go in and shout for him when the door opened and he stood there, frowning, like the irritated owner preparing to dismiss the latest itinerant duster seller.

‘What kept you?’ she asked.

He sat down to pull his boots on. ‘I didn’t know there was a time limit.’

She touched his shoulder. ‘Nothing,’ she said. ‘Which confirms it. We can only co-exist when we’ve reached each other’s Folly.’

He got up, shoved past her, walked away, toward the north garden.

‘You’re not going out?’ she said, pulling the door to.

‘What’s it to you?’

‘You can’t.’

He flung himself round – ‘Why, because I don’t belong here?’ – and stormed toward the side gate.

Ordinarily he would have stuck to the paths that swung through this part of the grounds, but as they were under snow he proceeded as if they’d never existed. Trailing approximately in his wake, Naia stuck to where she knew the paths to be, following her own and her mother’s earlier tracks between the kitchen garden and the wall that separated Withern from the old cemetery. Alaric was almost at the gate when he heard a tiny ringing sound. A young white cat had jumped down from the wall and was coming toward him, lifting each paw in turn clear of the snow. It reached him as he pulled the gate back, and wound itself around his calves, causing him to pause. When he stooped to coax the little creature away, it raised its head, perhaps in expectation of a tickle under the chin, and he saw the name on its collar. He looked closer to make sure he’d read correctly – he had – and said, ‘Oh, hilarious’ to Naia, still some yards behind, and went out in a hurry, slamming the gate after him. Naia stopped. What was that about? She watched the little cat pick its way across the garden, not understanding. Then she turned around and started back. Whatever it was, she could do without him in that mood.

In the lane beyond the gate Alaric had a choice. Turn left toward the river, or right, past the old primary school and to the high street. The high street might be a problem. In his village there were four shops: a newsagent’s, a bicycle repair shop, a small supermarket, and an art supplies shop. There were also two pubs and a Chinese takeaway. Curious as he was to see if everything was the same, he worried that he would bump into people he recognized but who would not know him. So he went the other way. The six-foot high wall on his left ran clear down to the river. Some months earlier, in his reality, a section of this wall had fallen in, or been pushed in. It hadn’t been repaired, so any casual stroller could see right across the north garden to the garage and the house. The wall on his left had not fallen at any point, or if it had it had been expertly restored. Another difference. Further cause for anger.

As he walked he was struck by the silence. It wouldn’t be noisy here anyway – no nearby roads, no people – but even so it was quieter than usual. The snow, of course. The snow lagged everything, muffled all sound. It was as if the everyday world had twisted just out of reach – as it had, in a way. He reached the end of the wall, and the river, and standing there his anger drained away. It was all so still. And perfect. The river was a broad white sheet that stretched without a single crease to the opposite bank, with its unruly thicket of winter trees and scrub, wild grasses, bent reeds, bulrushes. With the snow concealing so much, there was no noticeable difference between this stretch and his own. The only major discrepancies that he knew about were personal. Gazing out across the frozen water, he made the decision to confront the most profound of these at once. and turned; headed back the way he’d come.

He was passing the gate in the wall when a black-coated figure descended the cemetery steps some fifteen yards on and started toward him. He was tall, thin, elderly, and he walked oddly, like a young boy trying to ape the part of someone getting on in years. Alaric remembered him: the loiterer gazing at the house from the opposite bank the day all this started. But that was in his own reality, not Naia’s. This man might never have stood on that spot, never given this Withern Rise a moment’s attention or thought.

Alaric pulled his hood up as snow began to fall once more and he and the man drew near, their two pairs of feet scuffing the silence. They were about to pass when the man cleared his throat, compelling Alaric to glance his way in spite of his intention to avoid eye-contact. The man had very bright eyes, which were staring at him. There was something in that stare that made him uneasy. The unease was not alleviated by the words he heard as the man passed – ‘There’s just me’ – uttered in a curiously light, youthful voice thickened more by regret than age.

Reaching the cemetery steps, Alaric gl

anced back to make sure he wasn’t being pursued by the mad axeman of Eynesford. The man was standing on tiptoe trying to see over the wall into Withern’s garden.

Day Four / 6

Naia didn’t go back to the house. She was sick of being indoors, but she couldn’t leave the garden either. If she left the garden she would have to lock the door, and then Alaric wouldn’t be able to get in, which meant he would be unable to reach the Folly in her room and go home.

Before her lay the south garden. Old photos showed that there were once extensive flower beds here, and an apple tree and a pear. In one picture, taken in the early 1940s when Grandpa Rayner was little, a string hammock hung between the two trees. Both of them, along with the flower beds, had been removed by the non-Underwoods who lived there from 1947 to ’63. The Family Tree had survived only because it wasn’t in the way of the tennis court they wanted to put there. Luckily they’d opted for a grass court, but no one had played tennis here for decades so this part of the garden had ended up as nothing more than an empty lawn with that huge single tree. The crisp whiteness around the old trunk was disrupted only by the marks she and Alaric had made following his arrival, and the elongated lump of the bough that had snapped off some weeks ago. Naia cleared snow from the bough, sat down on it, dug her hands into her pockets, and tried to find some justification for Alaric’s boorishness.

He’d had a rough time of it. Mother taken from him, followed by two years of despair. She wouldn’t mind betting he’d lost some friends during that time. Who needs the company of such a misery? His school work had probably suffered too. Bad reports about his work and attitude seemed inevitable. She chided herself. How shallow to expect him to be an easy companion. He’d lost everything and seen for himself that she’d lost nothing. Quite the reverse. Oh. Of course! That was why he was in such a mood when he came out of the house. Her home was a palace compared to his. The differences must really have hurt. Just as well she hadn’t told him about the Lotto win. They didn’t often buy a ticket, the odds being so stacked, but about a year ago Mum had picked one up at the newsagent’s, and her numbers had come up. It wasn’t one of those massive multi-million jackpot wins, but it had paid for quite a bit of new furniture, and carpets, curtains, a decent bathroom and kitchen, and the Saab (three years old, but an infant compared to the ancient Daimler). They’d also had much of the house professionally decorated for the first time ever. There’d been no such improvements or additions at Alaric’s. No Lotto win. No Alex to buy the ticket.

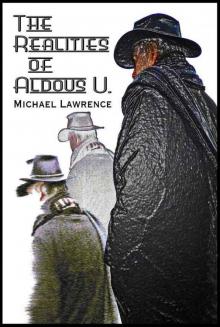

The Realities of Aldous U

The Realities of Aldous U